The increased integration of renewable technology will often be met through building services – in particular through alternatives to fossil fuel-based heating and cooling systems, like heat pumps.

And then there are innovations to consider where the building envelope actually incorporates renewable technology within itself. These can not only reduce heating and cooling demand, but also contribute to ventilation provision within commercial buildings.

Specifying building envelopes to avoid over-reliance on renewable technology

Before looking at examples of innovation, it’s important to put into context the way in which renewable technology is being embraced.

Previous versions of energy efficiency regulations – in particular, Part L in England – made it possible to achieve compliance by relying too heavily on renewable technology. The building fabric could be relatively poorly specified, with inefficiency being made up for by the inclusion of renewables.

Placing so much demand on the renewable technology meant it would likely not achieve its stated efficiency, its intended lifespan, or both. And with no imperative to maintain or repair systems that could be rapidly losing efficiency, buildings were responsible for much greater carbon emissions than predicted in compliance calculations.

Not only was the technology likely to be overworked, it often had to be oversized to compensate for the poor fabric performance. This made it a much costlier approach, in terms of both upfront costs and maintenance/servicing costs.

Subsequent versions of regulations have redressed this issue, placing greater emphasis on a fabric first approach. The adoption of fabric first means you can specify a smaller system and, by reducing the energy demand of the building through high performance building fabric, the system then doesn’t have to operate beyond its capacity.

As a result, the technology is more likely to achieve its stated performance, for a longer lifespan, and with lower maintenance needs.

Making the inclusion of solar PV part of building regulations

As part of the built environment’s journey to helping the country achieve its legally-binding net zero carbon target, updated building regulations are now featuring renewable technology more prominently. This is the case with Part L 2021 in England, which improves upon the fabric first approach of Part L 2013, and also significantly complements it with renewables.

For buildings other than dwellings, both the notional building specification and the worst-case ‘backstop’ U-values have been lowered, many of them quite significantly.

Alongside, there is also a requirement to accommodate solar PV panels. The amount of solar PV is determined based on a measure called the building’s ‘foundation area’. For side-lit buildings, an area of PV equivalent to 20% of the foundation area must be accommodated. In top-lit buildings, a minimum of 40% must be accommodated.

The only circumstance in which PV is not required is if a heat pump provides 100% of the space heating. Nevertheless, there are likely to be cases where all of the space heating demand is not met with a heat pump and it remains necessary to specify PV – for example, if only minimum fabric requirements are met.

The inclusion of PV panels that might not otherwise have been specified brings with it new considerations. Installation of the panels, and how they interact with the roof cladding, is one issue. There is also the question of maintenance, and how the panels will be accessed during the life of the building – and what that access means for the roof cladding.

An example of how manufacturers can support the increased adoption of PV arrays on commercial buildings is the change that Tata Steel has made to its 40-year Confidex® Guarantee. The guarantee covers pre-finished products like Colorcoat Prisma® or Colorcoat HPS200 Ultra®, and now includes cover for PV systems, mounted by clips or by fixings, on Colorcoat HPS200 Ultra® products.

What is a transpired solar collector?

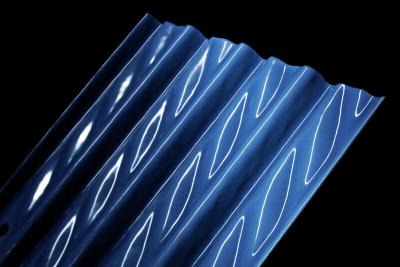

Accommodating renewable installations – like PV arrays – on and over the building envelope is one thing. But what about adapting the building envelope itself to provide both building fabric performance and renewable technology is a single panel?

An innovation being embraced by Tata Steel is the transpired solar collector. It forms part of a strategy where, having first followed a passive approach, the building design then implements complementary active solutions.

The micro-perforated active solar collectors draw in fresh air. Heat from the sun then warms that fresh air, and it can be used as a ‘pre-heater’ for the building’s blown air heating system. In short, the external envelope of the building becomes a means by which to absorb and ‘trap’ solar energy, and convert it into heat.

The system can meet around 30 to 40% – and up to 50% in the intermediate season – of daytime heating demand, with potential payback periods of less than five years. Not only that, but the free warm fresh air is a cost-effective solution to meeting new requirements for ventilation in Part F, especially where seeking to prevent viral infection in offices.

Contact us to learn more about the transpired solar collector, which can be incorporated as part of the Tata Steel Building Systems UK range of solutions. Alternatively, contact the Tata Steel building envelope team to find out how renewables can be incorporated into your next project, or to discuss guarantees like Confidex® and Platinum® Plus.